The Great Deception: Reclaiming Infrastructure as Code

Executive Summary

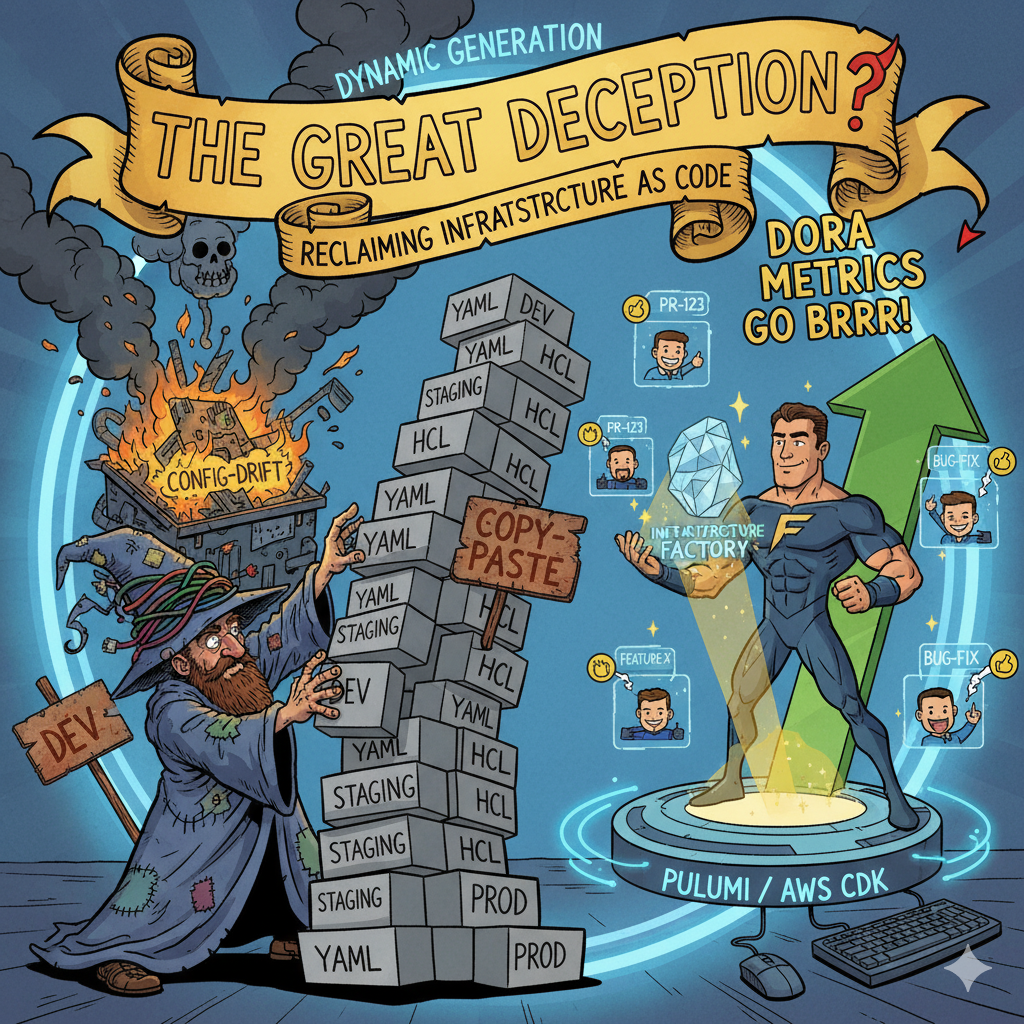

The modern practice of Infrastructure as Code (IaC) is predicated on a fundamental deception. While promising to bring the rigor and dynamism of software engineering to infrastructure management, the dominant paradigm has instead delivered Infrastructure as Static Configuration. This approach, characterized by version-controlled repositories filled with near-identical copies of declarative data files for dev, staging, and prod environments, is not an evolution but a lateral move. It replaces manual console operations with the equally manual and error-prone task of copying, pasting, and patching static text. This represents a catastrophic failure of abstraction that actively sabotages the core goals of DevOps: to deliver value faster and more safely.

The root of this deception lies in a cultural and philosophical schism between a traditional, state-oriented Admin Mindset and a modern, abstraction-oriented Software Engineering (SWE) Mindset. The tools that have achieved market dominance—Terraform, Helm, Kustomize—are built for the former. They excel at describing a target state but are fundamentally ill-equipped for the programmatic abstraction required to build dynamic, reusable systems. This forces practitioners into brittle workflows, guarantees configuration drift, creates debilitating development bottlenecks, and stifles innovation by making experimentation prohibitively expensive.

The necessary evolution is a paradigm shift toward the Infrastructure Factory. This model abandons the management of static files in favor of engineering a single, parameterizable software system. The entire infrastructure is defined as a function—create_environment(config)—that dynamically generates complete, isolated, and ephemeral environments on demand. This is not a theoretical fantasy; it is the native operational model of tools like Pulumi and the AWS Cloud Development Kit (CDK), which leverage the full power of general-purpose programming languages.

Adopting the Infrastructure Factory model is not a mere tooling change; it is a strategic imperative. It transforms the infrastructure team from manual provisioners into a high-leverage platform engineering function that delivers a self-service product to developers. This transition directly enables the creation of on-demand environments for every pull request, a capability that is the single greatest driver of elite DevOps performance as measured by the industry-standard DORA metrics. By moving from static configuration to dynamic code, organizations can finally break free from the great deception, unlocking unprecedented gains in development velocity, operational stability, security, and innovation. This report provides the technical blueprint and business case for this critical transformation.

Part I: The Anatomy of a Flawed Paradigm: Infrastructure as Static Configuration

The promise of Infrastructure as Code was to elevate infrastructure management to the level of a software engineering discipline, bringing with it the benefits of automation, versioning, and repeatability.1 However, the most common implementation of this promise has fallen critically short, regressing into a practice that more closely resembles meticulous data entry than creative software development. This section dissects the cultural origins of this flawed paradigm, examines its most pervasive anti-pattern, and quantifies the significant and often hidden costs it imposes on an organization.

1.1 The Cultural Chasm: Admin vs. Software Engineering Mindsets

The evolution of Infrastructure as Code did not occur in a vacuum. It emerged from the historical context of IT operations and software development, two disciplines with deeply ingrained, and often conflicting, worldviews.2 The current state of IaC can only be understood as a product of the tension between these two mindsets.

The Admin Mindset (State-Oriented)

The traditional systems administration role is fundamentally concerned with state. The primary responsibility is to configure, deploy, and maintain a specific set of resources—a server, a database, a network—in a known, stable condition.3 The artifact of this work has historically been a configuration file: an

httpd.conf, an XML document, or a series of manual steps documented in a runbook.4 The goal is the correctness and stability of a particular instance.

When this mindset is applied to modern cloud infrastructure, the artifact changes, but the philosophy does not. The .tf files of Terraform or the .yaml manifests of Kubernetes become the new configuration documents. The objective remains the same: to bring a specific environment (dev, staging, or prod) into a precisely defined target state. The infrastructure definition is treated as a sacred, static document to be carefully curated, managed, and replicated.

The Software Engineering Mindset (Abstraction-Oriented)

In contrast, the software engineering (SWE) discipline is fundamentally concerned with abstraction. A software engineer’s goal is not merely to solve a problem once, but to build a reusable, composable system that can solve an entire class of problems.5 The primary artifact is not a static configuration but a dynamic component: a function, a class, or a module. An engineer does not write the same logic ten times; they write one function and call it ten times with different parameters. The objective is to build a system capable of generating

any number of valid states based on variable inputs, hiding complexity behind well-defined interfaces.6

The Genesis of the Deception

The IaC movement, which began in earnest with the rise of cloud computing and tools like CFEngine, Puppet, and Chef in the mid-to-late 2000s, was an attempt to bridge these two worlds.2 It promised to apply SWE principles to infrastructure. However, the paradigm was largely co-opted by the deeply entrenched Admin Mindset. The tools that gained the widest adoption, most notably Terraform, succeeded because they offered a comfortable and familiar metaphor. They allowed operations teams to continue their work of managing configuration files, albeit with a more powerful, declarative syntax and an automated execution engine.7 This created the illusion of progress—infrastructure was now “code” because it was in text files stored in Git—but it failed to introduce the most critical element of the SWE mindset: true programmatic abstraction. The industry settled for automating the execution of static configurations rather than pursuing the more powerful goal of dynamically generating those configurations through software.

1.2 The “Folders-as-Environments” Anti-Pattern: A Dissection of Brittle Workflows

The most visible and damaging symptom of this philosophical compromise is the “folders-as-environments” repository structure. A typical IaC repository is organized with top-level directories named dev/, staging/, and prod/. Inside each, one finds a near-identical copy of the infrastructure definition, distinguished only by a handful of variables in a terraform.tfvars or values.yaml file. This structure is not a design pattern; it is an anti-pattern that institutionalizes manual, error-prone processes.

The Promotion Ritual

The process of moving a change through the software development lifecycle—from development to production—is called “promotion.” In this model, promotion is a literal, manual act of copying a block of HCL or YAML from one folder’s file and pasting it into another’s. This is not an act of engineering; it is a high-risk data entry task. Studies on manual data entry show that even with verification, human error rates can be as high as 4%, meaning four mistakes for every 100 entries.8 In the context of infrastructure, a single missed character during a copy-paste promotion can lead to catastrophic outages, security breaches, or compliance violations. This ritualistic, manual propagation of changes is a direct consequence of treating infrastructure definitions as distinct, static documents rather than instances generated from a single, authoritative codebase.

The Illusion of Version Control

While these configuration files are stored in a version control system like Git, the benefits of version control are severely undermined. The purpose of version control is to provide an atomic, auditable history of logical changes.1 In the folder-based model, a single logical change—such as updating the configuration of a database module—is not an atomic commit. It becomes a series of N separate commits across N different folders, each requiring a manual copy-paste operation.

This fragmentation has severe consequences:

- Loss of Auditability: It becomes incredibly difficult to track the history of a logical component. Answering the question “When did we change the database backup policy?” requires a painstaking forensic search across multiple, disconnected file histories.

- Inconsistent State: It is almost guaranteed that, over time, a change will be applied to dev and staging but forgotten or incorrectly applied to prod. This is a primary driver of configuration drift.9

- Impossible Rollbacks: A true rollback of a logical change is impossible. One cannot simply revert a single commit. Instead, a complex and equally error-prone manual process of reverting changes in multiple locations is required, often under the intense pressure of a production incident.

This anti-pattern is a clear indicator of low IaC maturity. It signifies that an organization has successfully automated the execution of infrastructure changes but has completely failed to automate the generation of the infrastructure definitions themselves. According to established IaC maturity models, this places such an organization firmly in the lower-middle “Managed” or “Defined” stages, where code exists but is tightly coupled and difficult to reuse, far from the “Optimizing” stage characterized by composable modules and dynamic environments.10

1.3 The High Cost of Stagnation: Quantifying the Damage

The folder-based, static configuration paradigm is not merely an aesthetic or philosophical failing; it imposes tangible, severe, and compounding costs on the organization. These costs manifest as increased risk, decreased productivity, and a chilling effect on innovation.

Configuration Drift: The Silent Killer of Stability

Configuration drift is the inevitable and often invisible divergence between the state of infrastructure as defined in version control and its actual state in the live environment.11 It is the most direct and dangerous consequence of the static configuration model.

- Causes of Drift: Drift is primarily caused by two factors inherent to this model. First, manual, out-of-band changes made directly in the cloud console or via CLI, often during high-pressure incident response, are not back-ported to the IaC repository.9 Second, the manual “promotion” process fails, and a change is not consistently propagated across all environment folders.9 The system has no inherent mechanism for self-correction; it relies on fallible human discipline, which breaks down under pressure.

- Tangible Consequences: The impact of unmanaged drift is severe. It creates unknown security backdoors, leads to compliance failures, and causes performance degradation and unexpected outages.11 A stark real-world example is the 2020 data breach at Twilio, which was attributed to the configuration drift of an S3 bucket. An engineer applied a security fix directly to a bucket, but this change was not reflected in the baseline IaC configuration. The drift went undetected for years until it was exploited by attackers, demonstrating how a seemingly minor inconsistency can escalate into a major security incident with significant financial and reputational costs.11

The Productivity Bottleneck: Sabotaging the Software Development Lifecycle (SDLC)

The static configuration model creates a structural bottleneck that slows down the entire software development lifecycle. The centerpiece of this bottleneck is the shared staging environment. Because provisioning a new, production-like environment is a slow, manual, and high-effort task, organizations are forced to funnel all pre-production testing through a single, shared, long-lived staging environment.

This has several negative effects:

- Merge Hell: The staging environment becomes a choke point. Multiple teams and features collide, leading to complex merge conflicts and a perpetually “dirty” state where it is impossible to isolate the impact of a single change.12 * Developer Toil and Context Switching: Developers must wait for their turn to use the shared environment, breaking their workflow and leading to costly context switching.13 It can take a developer 10-15 minutes to regain focus after an interruption, and a development process filled with these waits and blockages is profoundly inefficient.14 This queuing model is not merely inefficient; it is fundamentally flawed because there is no way to guarantee the shared environment is stateless. The naive assumption that changes can be tested sequentially ignores the reality of environment “pollution,” where one team’s deployment leaves behind modified data and altered configurations.13 This leads to flaky tests, “ghost” bugs, and a constant, blame-oriented effort to figure out “who broke staging”.

Impeding “Shift Left” Testing

The “Shift Left” movement in DevOps advocates for moving testing activities earlier in the development process to catch defects sooner, when they are cheaper and easier to fix.15 This requires the ability to test code against realistic, production-like environments from the very beginning of the development cycle—ideally, for every single commit or pull request.

The static configuration model makes this impossible. The cost and time required to manually create a full-stack environment for every branch is prohibitive. As a result, all early-stage testing is relegated to simulations against mocks or local environments that bear little resemblance to production.16 True integration testing is deferred until the code reaches the shared staging bottleneck, which is far too late in the process. This fundamentally undermines the primary goal of modern quality assurance and guarantees that bugs will be found later, when they are more expensive and disruptive to fix.

Stifled Innovation and the Prohibitive Cost of Experimentation

Perhaps the most insidious cost of the static model is the one that is hardest to measure: the innovation that never happens. When creating a new environment requires an engineer to spend days copying, pasting, and modifying hundreds or thousands of lines of configuration, the cost of experimentation becomes astronomically high.17

- The Economic Barrier: Teams are disincentivized from exploring new technologies or architectural patterns. A proposal to test a new database version, evaluate a different cloud service, or prototype a new microservice architecture is immediately met with the reality of the immense manual effort required to create an isolated testbed.

- The Technical Barrier: This leads to technological stagnation. The organization becomes locked into its existing patterns, not because they are the best, but because the activation energy required to change them is too great.18 The inability to rapidly and cheaply experiment prevents the organization from adapting to new challenges and seizing new business opportunities, ultimately eroding its competitive advantage.

Caging Developers: The Separation of App and Infra

A devastating consequence of the static GitOps model is the emergence of a risk-averse culture. Because the manual promotion process is so difficult and error-prone, teams learn to avoid changing the infrastructure whenever possible.19 The infrastructure becomes a static, untouchable layer, effectively kicked out of the application’s scope. This creates a new, more subtle bottleneck: developers become “caged” inside the container.20 They are free to change their application code, but they cannot easily request or implement changes to the underlying infrastructure that supports it. Need a new database version, a different sidecar, or updated networking rules? That requires a ticket to a specialized, overburdened DevOps team, leading to waits of days or weeks.20 This artificial separation prevents the application and its infrastructure from evolving together, stifling the adoption of new cloud services and ultimately limiting the application’s potential.

Part II: The Tooling Symptom: Declarative Data vs. Programmatic Abstraction

The flawed paradigm of Infrastructure as Static Configuration is not solely a cultural phenomenon; it is deeply intertwined with and enabled by the tools that dominate the industry. While these tools are powerful for their intended purpose—describing and reconciling a desired state—their fundamental design choices reinforce a data-centric worldview at the expense of true programmatic abstraction. This section critically analyzes the dominant toolchain and introduces the “Abstraction Ladder” as a framework for understanding the profound difference between managing infrastructure as data and engineering it as code.

2.1 Declarative by Design: The Terraform, Helm, and Kustomize Ecosystem

The most popular Infrastructure as Code tools are, by design, declarative data languages. They provide a syntax for describing what resources should exist, leaving the how of their creation to the tool’s engine.7 While this declarative nature is a strength for ensuring idempotency and managing state, the languages themselves are intentionally limited, which is the source of their weakness in abstraction.

Terraform (Infrastructure as Data)

Terraform’s core is its domain-specific language (DSL), HCL (HashiCorp Configuration Language). HCL is designed to be a structured configuration language, not a general-purpose programming language.21 Its primary metaphor is the

resource block—a static declaration of a piece of infrastructure.22 This makes Terraform exceptionally good at defining a target state graph and having its engine reconcile that state with the cloud provider.

However, this design choice creates significant limitations for abstraction:

- Limited Programmatic Logic: HCL has only rudimentary support for logic, such as conditional resource creation (count) and simple loops (for_each). Complex logic must be pushed into increasingly convoluted expressions or offloaded to external tools, making the code difficult to read, maintain, and test.12 * Weak Abstraction Mechanisms: Terraform’s primary abstraction mechanism is the module. While modules allow for grouping resources, they are essentially parameterized templates. As the need for flexibility grows, modules tend to suffer from “variable sprawl,” requiring an ever-expanding list of input variables to handle different edge cases, which erodes their simplicity.12 * Ineffective Environment Management: Terraform Workspaces are often presented as a solution for managing multiple environments, but they are little more than separate state files. They do not natively support environment-specific configurations or logic, forcing users back into complex conditional expressions or, more commonly, the folder-based anti-pattern.23 Essentially, working with Terraform is an act of authoring and manipulating a complex data structure (the resource graph) using a constrained language. It is Infrastructure as Data.

Helm (Glorified String Templating)

In the Kubernetes ecosystem, Helm is the de facto package manager. However, its abstraction mechanism is not based on code composition but on string templating.24 A Helm chart is a collection of YAML files interspersed with Go

text/template placeholders (e.g., ). The helm install command is a pre-processing step that performs a search-and-replace operation on these text files before sending the resulting YAML to the Kubernetes API.

This approach is a crude form of abstraction with significant drawbacks:

- No Composition: Helm charts do not compose in a programmatic sense. While one chart can depend on another, there is no way to create a new abstraction by combining and extending existing charts in code.

- Untyped and Unsafe: The templating is purely text-based. There is no type checking, no validation, and no IDE support for understanding the relationship between values and the template. A simple typo in a value name results in an empty string being injected into the YAML, often leading to silent failures or difficult-to-debug validation errors from the Kubernetes API server.

- Logic in Comments: To handle conditional logic, Helm forces developers to embed programming constructs like if blocks and range loops inside YAML comments (). This creates a hybrid language that is neither valid YAML nor valid Go, making it un-lintable, un-debuggable, and a maintenance nightmare.24 Helm is not code; it is a sophisticated

sed for the cloud-native era.

Kustomize (Data Patching)

Kustomize takes a different, and in many ways more honest, approach. It explicitly embraces the idea of infrastructure as data. It works by taking a “base” set of YAML manifests and applying a series of “overlays” or patches for each specific environment.24 This avoids the string-templating hell of Helm and is built directly into

kubectl, making it a lightweight option.

However, Kustomize fundamentally reinforces the static configuration mindset. The mental model is one of managing deltas between files. A change requires modifying the base and then ensuring the patches in each environment’s overlay still apply correctly. While it solves the problem of outright duplication, it still frames the task as the manual curation of static data files, not the execution of dynamic, generative code.

These tools—Terraform, Helm, and Kustomize—are not the root cause of the problem, but they are powerful enablers of it. They provide a path of least resistance for the Admin Mindset, allowing organizations to adopt a superficial form of IaC without making the necessary cultural and philosophical leap to a true software engineering approach.

2.2 The Abstraction Mechanism: Ascending the Ladder in IaC

To properly evaluate and contrast these different approaches, a more sophisticated framework than a simple feature comparison is needed. The Abstraction Ladder, a concept from semantics introduced by S.I. Hayakawa, provides a powerful mental model for reasoning about levels of abstraction in any system, including software.25 The ladder organizes concepts from the most concrete at the bottom to the most abstract at the top. Moving up the ladder involves asking “Why?” to generalize, while moving down involves asking “How?” to specify.26 This framework can be used to precisely map the capabilities of different IaC paradigms.

Mapping the IaC Abstraction Ladder

We can define a six-rung ladder for Infrastructure as Code:

- Rung 1: Concrete Instance. This is the lowest, most concrete level. It represents a specific, physical resource running in the cloud, with a unique ID, e.g., the S3 bucket named my-app-prod-assets-f1a2b3c. This is the “process-level” reality.

- Rung 2: Resource Definition. This is the first level of abstraction: a static block of code in a file that defines a single resource. This is the domain of a vanilla Terraform resource block or a single Kubernetes YAML file. It describes one specific thing.

- Rung 3: Templated Pattern. This rung represents a parameterized template that can generate multiple, similar resource definitions. A Terraform module or a Helm chart lives here. It abstracts a common pattern (e.g., a web service and a load balancer) but does so through data parameterization and text substitution.

- Rung 4: Composable Component. This is a critical leap. This rung represents a true software component—a class or a high-level function—that programmatically encapsulates a pattern of resources and their internal logic. Examples include a Pulumi ComponentResource or an AWS CDK L2/L3 Construct.27 A

PostgresDatabase component, for instance, would not just create a database instance but could also create the necessary security groups, parameter groups, and monitoring alarms, hiding this complexity from the consumer.28 * Rung 5: Application Stack Factory. At this level, we have a function that composes multiple Rung 4 components to define an entire, coherent application stack. This is the create_web_app(config) function. It takes high-level, business-relevant inputs (e.g., tier: “enterprise”, compliance: “pci”) and translates them into a complete graph of infrastructure components. - Rung 6: Platform Definition. The highest level of abstraction. This is the entire IaC codebase, viewed as a single software system. It represents the platform’s total capability to generate any environment for any application on demand, encoding all organizational best practices, security policies, and operational knowledge.

Why Declarative DSLs Struggle to Climb

This framework clearly illustrates the limitations of the data-centric paradigm.

- Terraform and Helm provide robust mechanisms to move from Rung 2 to Rung 3. This is the core value proposition of modules and charts.

- However, the leap to Rung 4 and Rung 5 is where these tools falter. Because they are not a general-purpose programming language, they lack the native constructs for true software composition. You cannot easily create a new component class that inherits from another and extends its functionality. You cannot write complex imperative logic to dynamically assemble components based on runtime conditions.

- Instead, all complexity must be forced down into the data model. To make a Terraform module more flexible (i.e., to climb the ladder), the only tool available is to add more input variables and more count/for_each expressions.12 The abstraction becomes leaky and brittle, resulting in modules with hundreds of inputs that are just as complex as the underlying resources they claim to simplify. They struggle to climb the ladder because their fundamental metaphor is the

file, not the function.

This distinction leads to a more accurate framing of the IaC debate. The conflict is not, as is often claimed, between declarative and imperative approaches. Programmatic tools like Pulumi and the AWS CDK are still declarative in their ultimate outcome; they produce a desired state graph that is handed to a reconciliation engine.22 The user does not write the sequence of API calls to create a resource.

The true distinction is between Infrastructure as Data and Infrastructure as Code. The former uses a constrained, data-centric language (like HCL or YAML) to define the state graph. The latter uses a rich, general-purpose programming language (like Python or TypeScript) to programmatically construct the state graph. This imperative construction phase allows for orders of magnitude more power, abstraction, and dynamism, enabling a smooth ascent to the highest rungs of the abstraction ladder. The so-called “hacks” of the data-centric world—Helm’s templating, Kustomize’s patching—are merely attempts to bolt on the missing programmatic capabilities that are first-class, intrinsic features of a true programming language. They are escape hatches that prove the insufficiency of the underlying model.

To crystallize this distinction, the following table provides a comparative analysis of the two paradigms across key dimensions.

| Dimension | Infrastructure as Data (Declarative DSLs) | Infrastructure as Code (General-Purpose Languages) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Metaphor | A document or file to be managed (e.g., main.tf, deployment.yaml). | A function or class to be executed (e.g., new VpcComponent()). |

| Abstraction Mechanism | Templating & Parameterization (Terraform Modules, Helm Charts). | Composition & Encapsulation (Pulumi Components, CDK Constructs). |

| Testing Capabilities | Limited to external tools for linting and integration testing (e.g., Terratest). Unit testing is difficult or impossible. | Native unit and property-based testing using standard language frameworks (e.g., Jest, Pytest). |

| Handling of Logic | Constrained logic via DSL constructs (count, for_each) or embedded in templates (). | Full expressive power of a general-purpose language (loops, conditionals, functions, classes, error handling). |

| Environment Management | Relies on file duplication (folder anti-pattern) or limited mechanisms like Workspaces. | A single codebase generates all environments by passing different configuration objects to a factory function. |

| Target Mindset | Admin Mindset: Focuses on defining and achieving a specific, static state for a known environment. | SWE Mindset: Focuses on building a dynamic, reusable system capable of generating any valid state. |

This table summarizes the core argument of this section: the choice of IaC tooling is not merely tactical but deeply strategic. It reflects and reinforces a fundamental mindset about how infrastructure should be managed, with profound consequences for an organization’s ability to scale, innovate, and achieve operational excellence.

Part III: The Solution: From Static Files to Dynamic Infrastructure Factories

Having dissected the flawed paradigm of Infrastructure as Static Configuration, the analysis now shifts to a comprehensive, architectural solution. The antidote to the brittleness and manual toil of the folder-based anti-pattern is a complete shift in mental model: from managing a collection of disparate documents to engineering a single, coherent Infrastructure Factory. This section provides the blueprint for this new paradigm, detailing its core principles, the enabling technologies that make it possible, and the transformative impact it has on the development workflow.

3.1 The New Paradigm: The create_environment(config) Function

The central principle of the Infrastructure Factory model is the radical consolidation of logic. Instead of scattering infrastructure definitions across numerous environment-specific folders, the entire infrastructure for all applications and all environments is defined within a single, version-controlled codebase. This codebase is structured as a software library, and its primary public API is a high-level function, conceptually create_environment(config).

This function serves as the single source of truth for infrastructure generation. It accepts a configuration object as its sole input and, upon execution, programmatically constructs and returns a complete, deployable definition for an entire application environment. This approach enforces a powerful separation of concerns that is impossible in the static model.

The Code (The Factory)

The core logic of the infrastructure is the “factory” itself. This code is written once and is completely agnostic of any specific environment like dev or prod. It is composed of a library of reusable, high-level components that represent logical parts of the architecture (e.g., a VPC, a KubernetesCluster, a WebAppService).6 These components are the building blocks that the factory function assembles.

This codebase is the exclusive domain of the platform or infrastructure engineering team. Their role shifts from fulfilling infrastructure requests to that of software engineers building a product. Their product is the infrastructure platform itself, and its features are the reusable components they build and maintain. This model transforms the infrastructure team into a high-leverage force multiplier for the entire organization. They are no longer a bottleneck for provisioning but enablers of developer self-service. By encoding organizational standards, security policies, and operational best practices directly into these reusable components, they create “golden paths” that allow application developers to build and deploy with speed and safety, without needing to become infrastructure experts.6

The Config (The Blueprint)

The “blueprint” for a specific environment is a simple, declarative data file, such as config.dev.json or config.prod.yaml. This file contains only the parameters that differ between environments: replica counts, instance sizes, domain names, feature flags, and other business-level configuration.29 This configuration file becomes the formal, stable interface between the platform team and the application developers. Developers can provision or modify an environment simply by editing this data file. They do not need to understand the underlying infrastructure logic. This dramatically reduces the cognitive load on developers, allowing them to focus on application features.30 For example, to scale up the web service in production, a developer simply changes

{ “webReplicas”: 3 } to { “webReplicas”: 5 } in config.prod.json and submits a pull request. The underlying complexity of modifying the autoscaling group or deployment resource is completely abstracted away by the factory.

3.2 The Enablers: Programmatic IaC with Pulumi and AWS CDK

This factory model is not just a theoretical construct; it is the native, idiomatic way of working with a modern class of IaC tools that embrace general-purpose programming languages. Pulumi and the AWS Cloud Development Kit (CDK) are the leading examples of this approach.

Pulumi: Treating Infrastructure as a Software Library

Pulumi allows teams to define, deploy, and manage cloud infrastructure using familiar languages like Python, TypeScript, Go, and C#.22 This is not merely a syntactic convenience; it unlocks the entire ecosystem of tools and practices from the software development world, including testing frameworks, package managers, and IDEs.

Pulumi’s core abstraction mechanism is the Component Resource. A component is a class that encapsulates a logical grouping of one or more underlying cloud resources into a single, reusable unit.31 This is the direct implementation of Rung 4 on the Abstraction Ladder. For example, a platform team can create a

StandardVPC component that provisions a VPC, public and private subnets across multiple availability zones, NAT gateways, and internet gateways, all according to company best practices. The consumer of this component simply instantiates it—new StandardVPC(“main-vpc”, {})—without needing to know about the two dozen underlying resources it creates.31 These components become the building blocks for the higher-level factory function.

AWS CDK: Composition with High-Level Constructs

The AWS CDK operates on a similar philosophy. It allows developers to define AWS infrastructure using languages like TypeScript and Python, which it then “synthesizes” into standard AWS CloudFormation templates for deployment.32 The CDK’s abstraction mechanism is the Construct. The AWS Construct Library provides a tiered system of these building blocks27:

- Level 1 (L1) Constructs: These are low-level, auto-generated classes that map one-to-one with CloudFormation resources. They provide strong typing but little abstraction.

- Level 2 (L2) Constructs: These are higher-level, human-authored classes that provide a much simpler, intent-based API for a single service. They come with sensible defaults, best-practice security policies, and boilerplate “glue logic” built-in. For example, creating a new s3.Bucket(this, ‘MyBucket’, { encryption: s3.BucketEncryption.KMS_MANAGED }) is far simpler than defining the equivalent L1 resources and IAM policies.

- Level 3 (L3) Constructs or Patterns: These are the highest level of abstraction, composing multiple L2 constructs to solve a common architectural pattern. A prime example is the aws_ecs_patterns.ApplicationLoadBalancedFargateService, which provisions a Fargate service, a task definition, a container, an Application Load Balancer, listeners, and target groups with a single instantiation.

The CDK ecosystem is built around the idea of creating and sharing these patterns, making it a natural fit for the Infrastructure Factory model.33 A platform team’s primary role becomes the creation of custom L2 and L3 constructs that encode the organization’s specific architectural and security standards.

3.3 The Workflow Revolution: On-Demand Environments for Every Pull Request

The true power of the Infrastructure Factory model is realized when it is integrated into the CI/CD pipeline. It unlocks a workflow that is impossible with the static configuration model: the creation of complete, production-like, ephemeral environments for every single pull request.

The Visionary Workflow

- A developer creates a feature branch (feat-new-login) and opens a pull request.

- This action triggers a CI/CD pipeline. The pipeline automatically generates a temporary configuration file on the fly (e.g., config.feat-new-login.json).

- The pipeline executes the infrastructure factory with this new configuration: my_iac_factory –config config.feat-new-login.json.

- This single command provisions a complete, full-stack environment—including its own dedicated database, message queues, and networking—fully isolated in a unique namespace or cloud account. The environment is accessible at a predictable URL, such as feat-new-login.company.com.

- The developer, QA engineers, and product managers can now test and review the feature against real, dedicated infrastructure. There is no more shared staging server, no more “it worked on my machine,” and no more testing against mocks.

- When the pull request is merged or closed, a webhook triggers a destroy command, and the entire stack—all of its resources and data—vanishes without a trace.

Implementation with Programmatic Tools

This workflow is a first-class, supported feature in modern programmatic IaC tools.

- Pulumi Review Stacks: Pulumi offers this capability out-of-the-box. By installing the Pulumi GitHub App, a repository can be configured to automatically create a new, temporary stack for each PR. The pulumi up command is run on PR creation, and the pulumi destroy command is run when the PR is merged or closed. The output of the deployment, including the environment’s URL, is posted as a comment directly on the pull request.34

- AWS CDK Dynamic Stack Creation: The same workflow can be implemented with the AWS CDK. The CI/CD pipeline can pass context variables, such as the Git branch name, to the cdk deploy command. The CDK application code can then read this context and use it to programmatically instantiate a new, uniquely named Stack object. For example, a PR for the feat-new-login branch would result in a CloudFormation stack named WebApp-feat-new-login. A post-merge step in the pipeline is then responsible for running cdk destroy on that uniquely named stack.35

The Transformative Impact

The ability to spin up on-demand environments is a paradigm shift for the entire development process.

- High-Fidelity Testing: It enables testing against an environment that is a true replica of production, dramatically increasing confidence in releases and reducing bugs.

- Elimination of Bottlenecks: It completely removes the shared staging environment as a choke point, allowing for true parallel development and testing.

- Increased Developer Velocity: Developers gain autonomy and can iterate much faster without waiting for infrastructure or worrying about impacting other teams.36

- Significant Cost Savings: By replacing long-lived, constantly running staging environments with short-lived, on-demand ones, organizations can drastically reduce their cloud infrastructure costs. Resources are only paid for during the few hours they are actively being used for testing and review.37 This workflow is the ultimate realization of the promise of DevOps. It is the lynchpin that connects a mature Infrastructure as Code practice to elite software delivery performance. The ability to create ephemeral environments on demand is the single most powerful technical capability for improving all four key DORA metrics—Deployment Frequency, Lead Time for Changes, Change Failure Rate, and Mean Time to Restore. It directly shortens lead times by removing bottlenecks, improves deployment frequency by enabling smaller and safer releases, slashes the change failure rate through high-fidelity testing, and reduces restoration time by ensuring every deployment originates from a known, version-controlled, and fully-tested state of the generative code.

Part IV: The Business Case: Measuring the Impact of True IaC

The transition from Infrastructure as Static Configuration to a dynamic Infrastructure Factory is not merely a technical upgrade; it is a strategic business investment with a clear and measurable return. Adopting a true software engineering approach to infrastructure directly impacts the metrics that define high-performing technology organizations. This section translates the technical benefits into a compelling business case, using industry-standard frameworks like DORA metrics and IaC Maturity Models to quantify the impact on delivery speed, stability, cost, and risk.

4.1 Accelerating Delivery: A DORA Metrics Analysis

The DevOps Research and Assessment (DORA) program has established four key metrics as the industry benchmark for measuring software delivery and operational performance. These metrics are not arbitrary; years of research have shown that elite performance in these areas is strongly correlated with superior organizational performance, including profitability, market share, and productivity.38 The Infrastructure Factory model is a direct and powerful driver for improving all four of these metrics.

- The DORA Framework:

- Throughput Metrics: Measure the velocity of software delivery.

- Deployment Frequency: How often an organization successfully releases to production.

- Lead Time for Changes: The time it takes a commit to get into production.

- Stability Metrics: Measure the reliability of the software delivery process.

- Change Failure Rate: The percentage of deployments causing a failure in production.

- Time to Restore Service (MTTR): How long it takes to recover from a failure in production.39 The static configuration model actively harms these metrics, creating bottlenecks that reduce throughput and introducing inconsistencies that degrade stability. The Infrastructure Factory model, by contrast, provides the foundational capabilities necessary for elite performance. The choice of IaC paradigm is a leading indicator of an organization’s potential to achieve high DORA scores. While DORA metrics are lagging indicators that measure past performance, the strategic decision to adopt a programmatic, factory-based model is a proactive investment that will causally lead to improved DORA outcomes.40 The following table details the causal chain from the specific pain points of the static model to the direct improvements enabled by the factory model for each DORA metric.

- Throughput Metrics: Measure the velocity of software delivery.

| DORA Metric | Pain Points with Static Configuration Model | Enabling Capability of Infrastructure Factory Model | Direct Impact on Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lead Time for Changes | Staging environment bottleneck; manual promotion process; long waits for infrastructure provisioning. | On-demand ephemeral environments; fully automated CI/CD pipeline for infrastructure. | Decreases |

| Deployment Frequency | Long lead times force large, infrequent, high-risk releases; fear of breaking the shared staging environment. | Small, incremental changes can be deployed and tested in isolation; increased confidence from automated testing. | Increases |

| Change Failure Rate | Environment drift between staging and prod; inability to perform high-fidelity testing early; manual copy-paste errors. | Guaranteed consistency between all environments; high-fidelity, full-stack testing on every pull request. | Decreases |

| Time to Restore Service (MTTR) | Difficult to identify root cause due to drift; rollbacks are complex, manual, and error-prone. | Infrastructure state is a direct, deterministic function of version-controlled code; rollbacks are as simple as redeploying a previous commit. | Decreases |

By directly addressing the root causes of friction and instability in the delivery process, the Infrastructure Factory model provides the technical underpinnings required to move from a low- or medium-performing organization to an elite one.

4.2 The IaC Maturity Model: Ascending to the Optimizing Stage

Another powerful framework for framing this transition is the Infrastructure as Code Maturity Model. This model describes a five-stage journey that organizations typically follow as they adopt and refine their IaC practices.10

- Level 1: Initial: No IaC. All infrastructure is managed manually through cloud consoles or ad-hoc scripts. Processes are chaotic and unrepeatable.

- Level 2: Managed: Some automation and IaC are in place, but code is often tightly coupled to specific projects and difficult to reuse. Some manual management persists.

- Level 3: Defined: Infrastructure is fully defined in version-controlled code, which is considered the source of truth. Key processes are automated, and new environments can be created consistently, though it may still be a largely manual process to initiate.

- Level 4: Measured: Infrastructure code is modularized into reusable components and peer-reviewed. Automated testing is in place. Access to systems is restricted, and operations are integrated into the development lifecycle. Ad-hoc environments can be created and destroyed easily.

- Level 5: Optimizing: Core infrastructure is defined as versioned, packaged, and reusable modules consumed by application teams. Dynamic environments are created and destroyed automatically as part of the CI/CD process for testing. Best practices are continuously shared and improved through the codebase.

This model clearly illustrates the strategic ceiling imposed by the static configuration paradigm. The “folders-as-environments” approach allows an organization to reach Level 3, “Defined,” at best. They have their infrastructure in code, but it is not reusable, composable, or dynamic. It is a dead end.

The Infrastructure Factory model is the very definition of the “Optimizing” stage. It is built on a foundation of reusable, composable components (Level 4) and fully automates the creation and destruction of dynamic environments for testing (Level 5). Therefore, the decision to adopt a programmatic IaC approach is a conscious, strategic decision to ascend the maturity model and unlock the full potential of Infrastructure as Code.

4.3 Real-World Impact: Case Studies in Productivity, Cost, and Stability

The benefits of this paradigm shift are not merely theoretical. They are demonstrated in real-world case studies and supported by quantitative data on developer productivity, cost savings, and security posture.

Productivity Gains

The primary goal of the Infrastructure Factory is to reduce the cognitive load on application developers and remove infrastructure as a bottleneck. By providing a self-service platform with simple, high-level abstractions, it allows developers to focus on delivering business value.

- A compelling case study is Starburst’s migration from Terraform to Pulumi. Under their previous Terraform-based, static model, a single blue-green deployment across all regions was a two-week process involving numerous manual steps and fragile glue scripts. This severely limited their delivery velocity and ability to expand into new markets. By adopting a programmatic approach with Pulumi, they were able to fully automate this process, reducing deployment times from two weeks to a matter of hours. This was not just an efficiency gain; it was a critical enabler of their business growth.41

- While direct studies on programmatic IaC productivity are emerging, we can look at adjacent fields like AI-assisted development for a quantitative proxy of the impact of high-leverage tooling. A large-scale, one-year study of an in-house AI platform found that its adoption led to a 31.8% reduction in pull request review cycle time and a 61% increase in code volume pushed to production by top adopters.42 The Infrastructure Factory provides a similar leverage effect, automating away entire classes of manual work and review.

Cost Optimization

The static configuration model is economically inefficient. It necessitates long-running, underutilized staging and development environments that generate significant cloud costs. The ephemeral, on-demand environments enabled by the Infrastructure Factory model offer a fundamentally more efficient pay-per-use economic model.37

- Elimination of Cloud Waste: Environments only exist for the duration of a pull request review, typically a few hours or days, rather than running 24/7. This directly translates to massive reductions in cloud spend for non-production environments.43

- Reduction of Hidden Labor Costs: The automation inherent in the factory model eliminates the significant “hidden labor” costs associated with manual infrastructure management, error correction, and debugging issues caused by environment drift.18

Enhanced Security and Compliance

In the static model, security is often a reactive process of auditing and remediation. The Infrastructure Factory model allows security and compliance policies to be “shifted left,” embedding them directly into the reusable components that developers consume.

- Security by Default: A platform team can build a SecureS3Bucket component that has encryption, versioning, access logging, and private-only access policies enabled by default. Application developers can then use this component without needing to be experts in S3 security.44

- Automated Governance: Policies can be written as code and executed as automated tests within the CI/CD pipeline. For example, a policy could ensure that no database is ever provisioned without backups enabled, or that no resource is created without the proper cost-center tags. This provides a consistent, scalable, and auditable enforcement of security and governance rules, preventing entire classes of misconfiguration errors before they ever reach a live environment.45 Ultimately, the business case for the Infrastructure Factory model rests on a simple premise: it addresses the systemic sources of risk and inefficiency in the software delivery process. It is an investment in a platform that enables speed, stability, and security by design, rather than by heroic effort and manual discipline. This is a strategic shift that moves an organization from constantly reacting to infrastructure problems to proactively engineering them out of existence.

Part V: Strategic Recommendations and a Roadmap for Transition

The transition from a static, data-centric IaC model to a dynamic, programmatic Infrastructure Factory is a significant architectural and cultural undertaking. It requires a deliberate strategy, a commitment to developing new skills, and a phased approach to implementation. This final section provides actionable guidance for technology leaders to navigate this transformation successfully, fostering the right culture, executing a pragmatic migration, and making principled technology choices.

5.1 Fostering an Infrastructure Software Engineering Culture

The most critical prerequisite for success is a cultural shift. The technology is an enabler, but the mindset is the foundation. Organizations must consciously move away from the traditional “Ops” model of ticket-based fulfillment and toward a modern “Platform Engineering” model.46

Redefining Roles and Responsibilities

The team responsible for infrastructure must be redefined as a Platform Engineering team. Their mission is not to manually provision resources for other teams, but to build, maintain, and support a self-service internal developer platform.46 This platform—the collection of reusable IaC components, CI/CD pipelines, and factory functions—is their product. The application developers are their customers. This product-oriented mindset is crucial; it aligns the platform team’s incentives with developer productivity and organizational velocity. Success is measured not by tickets closed, but by the speed and autonomy of the application teams they enable.

Investing in Software Engineering Skills

This new mission requires a new set of skills. Platform engineers are not just sysadmins who can write scripts; they are software engineers whose domain is infrastructure. Organizations must invest in training and hiring for core software engineering competencies within the platform team, including47:

- Software Design Patterns: Understanding concepts like abstraction, encapsulation, and composition is essential for building robust and maintainable components.

- API Design: The inputs to the reusable components and factory functions are the API of the platform. Designing these interfaces to be simple, intuitive, and progressively complex is a critical skill.

- Automated Testing: A deep understanding of unit, integration, and end-to-end testing is required to build a reliable platform. The platform’s components must be as rigorously tested as any application code.

- Version and Dependency Management: The platform’s components will be versioned and consumed as packages by application teams, requiring a disciplined approach to semantic versioning and managing breaking changes.

Bridging the Divide Through Code

The Infrastructure Factory model provides a powerful mechanism for collaboration between platform and application teams. The platform’s codebase, particularly the high-level components it exposes, becomes the formal, version-controlled contract between the two groups. Application developers can contribute to the platform by opening pull requests, suggesting new features for components, or even building their own components for shared use, all subject to the same code review and testing standards as the core platform itself. This fosters a shared sense of ownership and breaks down the traditional silos between “dev” and “ops.”

5.2 A Phased Transition Strategy: From Static Repositories to Dynamic Factories

A “big bang” migration is rarely feasible or wise. A pragmatic, phased approach allows an organization to build momentum, demonstrate value, and manage risk throughout the transition. The goal is to incrementally climb the IaC Maturity Model.10

- Phase 1: Standardize and Consolidate (Achieving “Defined” Maturity). The first step is to tame the existing chaos. Even within a static Terraform environment, significant improvements can be made.

- Action: Identify all duplicated HCL across the dev/, staging/, and prod/ folders.

- Action: Refactor this duplicated code into standardized, reusable Terraform modules with clear inputs and outputs.

- Action: Centralize these modules in a dedicated Git repository, consumed by all environment configurations.

- Outcome: This phase does not change the core tooling but eliminates the worst of the copy-paste anti-pattern. It establishes a single source of truth for infrastructure patterns, even if the environment definitions themselves are still separate.

- Phase 2: Wrap and Abstract (Beginning the Transition). Introduce a programmatic IaC tool (e.g., Pulumi, AWS CDK) in a non-disruptive way.

- Action: Use the programmatic tool’s ability to interoperate with the existing tools. For example, Pulumi can consume and manage Terraform modules directly.

- Action: Begin building higher-level programmatic components that wrap the existing, battle-tested Terraform modules. This starts to build the factory’s component library while leveraging existing assets.

- Outcome: A new, more powerful abstraction layer is created on top of the existing infrastructure code. Developers can start consuming these simpler components for new services, while legacy services remain untouched.

- Phase 3: Build and Migrate (Reaching “Measured” Maturity). With the new programmatic tool in place, begin building new infrastructure patterns natively.

- Action: For all new services and features, create native components directly in the programmatic language (e.g., new Pulumi Components or CDK Constructs).

- Action: Develop a plan to incrementally migrate existing services from the old static configurations to the new programmatic factory model. This can be done one service at a time to minimize risk.

- Outcome: The organization’s infrastructure is now managed by a hybrid system, with a clear strategic direction to move everything to the new, more mature model. The ability to create ad-hoc environments programmatically is now possible.

- Phase 4: Automate and Optimize (Achieving “Optimizing” Maturity). The final phase is to fully realize the benefits of the factory model by integrating it deeply into the development workflow.

- Action: Implement the on-demand, ephemeral environment workflow in the CI/CD pipeline for every pull request, as described in Part III.

- Action: Decommission the old, long-lived shared staging environments.

- Outcome: The transformation is complete. The infrastructure platform operates as a fully automated, dynamic factory. The organization has reached the highest level of IaC maturity, enabling elite DevOps performance.

5.3 A Principled Approach to Tool Selection

The choice of tool is a critical enabler of this strategy. While a detailed tool-by-tool comparison is beyond the scope of this report, the analysis provides a clear set of principles for making this decision.

- Philosophical Alignment: The most important criterion is the tool’s core philosophy. Does its primary metaphor treat infrastructure as static data to be managed, or as dynamic software to be engineered? For organizations committed to the factory model, only tools that fall into the latter category should be considered.

- The Right Tool for the Right Scale: Acknowledge that there is no one-size-fits-all answer. For a small team with a single, simple application, the overhead of a full programmatic model may not be justified; the simplicity of a declarative DSL like Terraform might be a perfectly rational choice. However, for any organization with multiple teams, multiple services, and ambitions to scale and innovate rapidly, the limitations of the data-centric model will quickly become a strategic liability.

- Key Evaluation Criteria: For organizations pursuing the factory model, the evaluation should focus on:

- Programming Model Richness: How well does the tool support the features of the chosen language? Does it enable clean abstractions, testing, and use of the existing package ecosystem?

- Component Framework: How mature and powerful is the tool’s mechanism for creating reusable components (e.g., Pulumi Components, CDK Constructs)? Does it support cross-language consumption to allow the platform team to build in one language while developers consume in another?

- Ecosystem and Community: How extensive is the provider support, and how active is the community in building and sharing reusable patterns?

Under these criteria, tools like Pulumi and the AWS CDK represent the current state-of-the-art. They are explicitly designed around the software engineering principles required to build a true Infrastructure Factory. While they present a steeper initial learning curve for the platform team compared to a simple DSL, this is a strategic investment in centralizing complexity. This investment pays dividends by drastically reducing the cognitive load and friction for the entire application development organization, ultimately unlocking the speed, stability, and innovation that was the original promise of Infrastructure as Code.

Works cited

-

Infrastructure as Code : Best Practices, Benefits & Examples – Spacelift, accessed September 29, 2025, https://spacelift.io/blog/infrastructure-as-code ↩ ↩2

-

Entire history of Infrastructure as Code. – devopsbay, accessed September 29, 2025, https://www.devopsbay.com/blog/entire-history-of-infrastructure-as-code ↩ ↩2

-

Infrastructure as code: a journey through time – Aardwark, accessed September 29, 2025, https://aardwark.com/en/infrastructure-as-code-a-journey-through-time/ ↩

-

Infrastructure as code – Introduction to DevOps on AWS, accessed September 29, 2025, https://docs.aws.amazon.com/whitepapers/latest/introduction-devops-aws/infrastructure-as-code.html ↩

-

What is Infrastructure as Code? – IaC Explained – AWS, accessed September 29, 202.5, https://aws.amazon.com/what-is/iac/ ↩

-

Golden Paths in IDPs: A Complete Guide to Reusable Infrastructure with Pulumi Components and Templates, accessed September 29, 2025, https://www.pulumi.com/blog/golden-paths-infrastructure-components-and-templates/ ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

What is Infrastructure as Code (IaC)? – Red Hat, accessed September 29, 2025, https://www.redhat.com/en/topics/automation/what-is-infrastructure-as-code-iac ↩ ↩2

-

7 Human Error Statistics For 2025 – DocuClipper, accessed September 29, 2025, https://www.docuclipper.com/blog/human-error-statistics/ ↩

-

Top 7 IaC Pitfalls – Risks, Challenges, Solutions – Daily.dev, accessed September 29, 2025, https://daily.dev/blog/top-7-iac-pitfalls-risks-challenges-solutions ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

The IaC Maturity Model, accessed September 29, 2025, https://kenmuse.com/blog/the-iac-maturity-model/ ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

How to Detect and Prevent Configuration Drift In IaC – Snyk, accessed September 29, 2025, https://snyk.io/articles/infrastructure-as-code-iac/detect-prevent-configuration-drift/ ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Should you use the same IaC code to deploy to dev/staging/prod or copy paste it? – Reddit, accessed September 29, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/Terraform/comments/1bk2h0i/should_you_use_the_same_iac_code_to_deploy_to/ ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

The Hidden Costs of Traditional Staging Environments Across the …, accessed September 29, 2025, https://release.com/blog/hidden-costs-of-staging ↩ ↩2

-

Context-switching is the main productivity killer for developers : r/programming – Reddit, accessed September 29, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/programming/comments/1ij60ba/contextswitching_is_the_main_productivity_killer/ ↩

-

What is Shift-left Testing? IBM, accessed September 29, 2025, https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/shift-left-testing -

Shift-Left – Testing, Approach, & Strategy – New Relic, accessed September 29, 2025, https://newrelic.com/blog/best-practices/shift-left-strategy-the-key-to-faster-releases-and-fewer-defects ↩

-

The True Cost of Experimentation, accessed September 29, 2025, https://statsig.com/blog/the-true-cost-of-experimentation ↩

-

5 infrastructure as code examples Key use cases and benefits of IaC Lumenalta, accessed September 29, 2025, https://lumenalta.com/insights/5-infrastructure-as-code-examples -

GitOps Effects On Developer Experience – Port.io, accessed September 29, 2025, https://www.port.io/blog/gitops-effects-on-developer-experience ↩

-

Developer-Driven Infrastructure: Breaking the DevOps Bottleneck by Nicholas Thoni, accessed September 29, 2025, https://medium.com/@nicholasthoni/developer-driven-infrastructure-breaking-the-devops-bottleneck-848a611ab77b -

The Developer’s Guide to HCL, Part 1: Introduction – Scalr, accessed September 29, 2025, https://scalr.com/learning-center/the-developers-guide-to-hcl-part-1-introduction/ ↩

-

Pulumi vs. Terraform : Key Differences and Comparison – Spacelift, accessed September 29, 2025, https://spacelift.io/blog/pulumi-vs-terraform ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Terraform Workspaces vs. Terragrunt: Which Should You Choose for Multi-Environment Management? by Gouravmishra Medium, accessed September 29, 2025, https://medium.com/@gouravmishra624/terraform-workspaces-vs-terragrunt-which-should-you-choose-for-multi-environment-management-48f389679b84 -

Helm vs. Kustomize: Why Not Both? Choosing the Right Tool for Kubernetes Configuration Management – KoalaOps, accessed September 29, 2025, https://www.koalaops.com/blog/helm-vs-kustomize-why-not-both ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

The Abstraction Ladder W.J. Warren, accessed September 29, 2025, http://blog.ansuz.nl/index.php/2023/02/21/the-abstraction-ladder/ -

Abstraction Laddering – Open Practice Library, accessed September 29, 2025, https://openpracticelibrary.com/practice/abstraction-ladder/ ↩

-

AWS CDK Constructs – AWS Cloud Development Kit (AWS CDK) v2 – AWS Documentation, accessed September 29, 2025, https://docs.aws.amazon.com/cdk/v2/guide/constructs.html ↩ ↩2

-

The Case for Abstractions in IaC – Massdriver, accessed September 29, 2025, https://www.massdriver.cloud/blogs/the-case-for-abstractions-in-iac ↩

-

Configuration Pulumi Concepts, accessed September 29, 2025, https://www.pulumi.com/docs/iac/concepts/config/ -

Reducing Developer Cognitive Load with Platform Engineering – DevOpsCon, accessed September 29, 2025, https://devopscon.io/blog/developer-cognitive-load-problem/ ↩

-

Component Resources Pulumi Docs, accessed September 29, 2025, https://www.pulumi.com/docs/iac/concepts/components/ -

AWS Cloud Development Kit (CDK) vs. Terraform – Spacelift, accessed September 29, 2025, https://spacelift.io/blog/aws-cdk-vs-terraform ↩

-

Developing enterprise application patterns with the AWS CDK, accessed September 29, 2025, https://aws.amazon.com/blogs/devops/developing-application-patterns-cdk/ ↩

-

Pulumi Review Stacks, accessed September 29, 2025, https://www.pulumi.com/docs/pulumi-cloud/deployments/review-stacks/ ↩

-

Stacks in AWS CDK, accessed September 29, 2025, https://docs.aws.amazon.com/cdk/v2/guide/stacks.html ↩

-

What is developer velocity and how do you measure it?, accessed September 29, 2025, https://www.atlassian.com/blog/teamwork/what-is-developer-velocity-and-how-do-you-measure-it ↩

-

How Ephemeral Test Environments Solve DevOps’ Biggest Challenge – Perforce Software, accessed September 29, 2025, https://www.perforce.com/blog/pdx/ephemeral-test-environments ↩ ↩2

-

DORA’s software delivery metrics: the four keys, accessed September 29, 2025, https://dora.dev/guides/dora-metrics-four-keys/ ↩

-

DORA’s software delivery metrics: the four keys, accessed September 29, 2025, https://dora.dev/guides/dora-metrics-four-keys/ ↩

-

Accelerate State of DevOps Report 2023 – DORA, accessed September 29, 2025, https://dora.dev/research/2023/dora-report/ ↩

-

Starburst’s Migration to Pulumi, accessed September 29, 2025, https://www.pulumi.com/case-studies/starburst/ ↩

-

Intuition to Evidence: Measuring AI’s True Impact on Developer Productivity – arXiv, accessed September 29, 2025, https://arxiv.org/html/2509.19708v1 ↩

-

Cloud Waste Management: A Guide to Reducing Your Cloud Bill, accessed September 29, 2025, https://www.cloudhealthtech.com/blog/cloud-waste-management-guide ↩

-

Security by Default in Infrastructure as Code, accessed September 29, 2025, https://www.cncf.io/blog/2022/09/21/security-by-default-in-infrastructure-as-code/ ↩

-

Adopting Infrastructure as Code (IaC) for Secure and Efficient Deployments – CIO Influence, accessed September 29, 2025, https://cioinfluence.com/cloud/adopting-infrastructure-as-code-iac-for-secure-and-efficient-deployments/ ↩

-

Puppet’s 2024 State of DevOps Report Reveals Security is Strengthened by Platform Engineering Perforce Software, accessed September 29, 2025, https://www.perforce.com/press-releases/2024-state-devops-report -

What is a Platform Engineer? And What Skills Do You Need?, accessed September 29, 2025, https://port.io/blog/platform-engineer-skills ↩